dürer in italy

Already after his first trip to Italy (1494–95) but before the turn of the century, Dürer began to determine the shape of the human being geometrically. In working on portraits, including of himself, he relied on equidistances. He developed these out of linear grids as magnitudes relating to the division of the face into three parts (see Before 1500).

In Dürer’s self-portrait in Madrid (here only one side of the proportion diagram has been drawn in), red lines show that identical distances are adhered to in three directions from the tear duct of the left eye. At the same time this eye is bordered exactly by the diagonals of the central field.

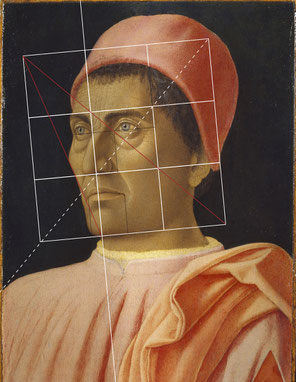

Dürer could have observed the manner of refining the facial features in the work of the Italian painter Andrea Mantegna (1431 – 1506). Mantegna also based his Portrait of Cardinal Carlo de’ Medici on a construction, for example.

Within the quadratic net of nine fields, black lines show identical distances in the face. Here they proceed not only from one corner of the eye, but also mark the height of the corner of the mouth and the height of the edge of the hat on one line of the grid.

That an ordering proportional diagram can also be presumed in the case of Mantegna is attested to by other, dependent construction lines as well. A red one grazes the cheekbone, another cuts through the tear duct of the eye. The white dotted line begins at the lower left on the shoulder and traverses the whole linear framework.

In both works it is striking that the grid also incorporates the head coverings. In Dürer’s self-portrait it is a fold in his two-coloured pointed cap that indicates the starting point of his construction. Between it and one of the inner corners of the eye, a vertical line runs towards the chin. The tripartite division of the face is carried out along this line, its unit being the distance from the left outer corner of the eye to the right-hand edge of the face.