Italy as Model? Mantegna and Bellini

During his first stay in Italy Dürer encountered the art of Mantegna (see Dürer in Italy), whose works he copied, as well as the painting of Giovanni Bellini (1437 – 1516), among others. He learned the current art of Venice at the time “to the point of complete mastery”. [1]

Mantegna supposedly even praised Dürer’s virtuosity. The only contemporary remark about this comes from Joachim Camerarius (1500 – 1574), who pointed out at the same that Mantegna returned “painting to a certain strictness and rule-boundedness.” [2]

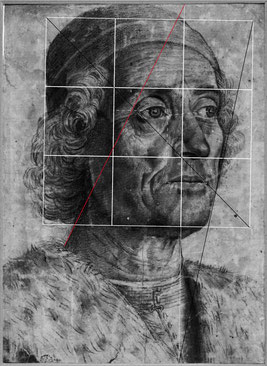

For this reason, it can be assumed that in his study of the Italian artists, Dürer also came into contact with issues of measurement aesthetics. Construction examples have been drawn up for the works by Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini – with whom Dürer was on friendly terms [3] – illustrated here.

They begin with a Vitruvian tripartite division of the face. In the case of the doge, it is extended upwards by the same basic unit and ends at the apex of the cap known as the ‘corno ducale’.

For both works it can be determined that the quadratic net provides lynchpins for the entire composition. I his head constructions, Dürer too made use of construction lines that incorporated the sitter’s surroundings (see Before 1500).

In Mantegna’s Portrait of a Man a (black) line runs from the upper right corner along the cheekbone down to a vertical line drawn to the bottom. A diagonal exactly grazes one corner of

an eye and corner of the mouth in the face. Another line (red) runs along the throat and meets the vertical line just mentioned at the upper edge of the image. [4]

In Bellini’s Portrait of the Doge Leonardo Loredan the use of an internal circle is notable, its radius seeming to specify measurements of the face and the cap. Striking are also the red

lines, one of which ‘nestles’ along the face, another traces the shoulder, and a further one meets the cap at a prominent point. Two lines run together at the point where the row of buttons

begins on the high-collared robe.

[1] Johann Konrad EBERLEIN, Albrecht Dürer (Reinbek bei Hamburg, 2003), 20; cf. Fritz KORENY, Dürer e Venezia, in: exhib. cat.

Il Rinascimento a Venezia e la pittura del nord ai tempi di Bellini, Dürer, Tiziano, Padua, ed. by Bernard Aikema / Beverly Louise Brown, 26 January–16 July 1999, 240-49, esp.

241.

[2] Camerarius translated theoretical works of Dürer’s into Latin. Quoted from: Thomas SCHAUERTE, Dürer. Das ferne Genie. Eine

Biographie (Stuttgart, 2012), 58–59: Dürer’s virtuosity “(...) räumte mit offensichtlichem Freimut auch Andrea Mantegna ein, der in Mantua hohes Ansehen genoß; er hatte die Malerei zu einer

gewissen Strenge und Gesetzlichkeit zurückgeführt (....).”; see also Marzia FAIETTI, ‘Aemulatio versus simulatio. Dürer oltre Mantegna’, in exhib. cat. Dürer e l'Italia, Scuderie del Quirinale /

Rome, 10 March–10 June, 2007, ed. by Kristina Herrmann Fiore (Milan, 2007), 81–87, here 81.

[3] Dürer was pleased to report on a meeting with the old painter in a letter from 7 February 1506. Hans RUPPRICH, Dürer.

Schriftlicher Nachlass, Bd. 1, Berlin 1956, 44; see also Édouard POMMIER, ‘Dürer e il ritratto italiano’, in exhib. cat. Dürer e l'Italia, Scuderie del Quirinale / Rome, 10 March–10 June, 2007,

ed. by Kristina Herrmann Fiore (Milan, 2007), 105–08, esp. 106.

[4] A similar system of lines that mediate between linear grid and image format to

describe the face can also be discerned in the Portrait of a Man with Black Cap (Musée des Beaux-Arts et d'Archéologie, inv. no. D.3103), attributed to Mantegna. See both works in exhib.

cat. Andrea Mantegna, Royal Academy of Arts / London, 17 January–5 April 1992 and The Metropolitan Museum of Art / New York, 9 May–12 July 1992, ed. by Jane Martineau (London, 1992), cat. nos.

106, 107.